#Persian Wars

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

If you were to travel back in time to Ancient Greece, what year would you pick and why?

A specific year? I suppose at some point between 440 - 399 BC during Socrates' peak. He is one of the most intriguing Ancient Greek historical figures to me. I would like to see first hand what and how he taught. In the same time span, I would be able to also meet Democritus and see how he developed his atom theory.

Alternatively, in 479 BC the year in which the Battles of Platea and Mycale against the Persians took place, supposedly in the very same day, and it was essentially the final victory against the Persian invasion. I suppose that must have been a very euphoric year to live in, full of hope after the despair of Thermopylae one year prior.

And if I stayed there for five-ten years after 479 I would also be able to see Pericles in his prime, cos I kinda have a crush on him.

#greece#history#ancient greek history#socrates#persian wars#battle of platea#democritus#battle of mycale#greek history#pericles#nickisgirl#ask

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

What should we make of Alexander I and Perdiccas II both having long 40+ years long reigns, only for all of their successors having substantially shorter ones? And, if you are in the mood, who do you think was the better ruler between the two?

Alexander I and Perdikkas II

First, I thought I’d mention one of the cool things to come out of the recent ATG conference is a plan to produce an edited collection: Alexander I and the Making of Macedon. It’ll be a while, but if I can get us a publisher, I’ve got the contributors.

Also of note, Sabine Müller and Johannes Heinrichs are producing a monograph on Alexander I in English. She has a great one on Perdikkas but it’s in German, so I was very happy to hear this.

Finally, I've got a number of racked-up Asks. This answer will answer about three of them. I'll link it to the other questions. :-)

To the questions: it’s really hard to compare Alexander I and Perdikkas II simply because they were dealing with very different circumstances. Alexander I had Persian assistance holding the throne, while Perdikkas was tossed off his throne at least once.

The biggest difficulty is a source problem. ALL our info about these guys (outside archaeology) comes from Greeks, who were chiefly interested in them only when they intersected with the southern Greek world. There’s a fair bit about Alex I’s internal politicking that we just don’t know. What we call “Lower Macedon” probably only goes back a couple generations, despite the mythical king list. We find a MARKED change in burial practices c. 570 BCE, which is before Persians were mucking around up there. This suggests a change—or more likely consolidation—in the lowland Macedonian ruling elite, both west and a bit east of the Axios River.

If Alexander I took over c. 500-495 (coin above), and his father Amyntas (about whom we know nothing but a name) ruled for 20/30-ish years before, then Alexander’ grandfather (Alketas) or great-grandfather (Airopos) would have consolidated the area around Aigai. Yet ALL names before Amyntas I are essentially fictional. Certainly the “founder’s” name changed across time. It’s Perdikkas when we first hear of it in Herodotos, but may have shifted to Archelaos later (see Euripides’s play of that name). Later yet (under Philip), it seems to have become Karanos. If Bill Greenwalt’s theories are right. This is not a real person in any historical sense.

The problem with dating Alexander I is that we neither know for sure when he took the throne nor when he died. It was convenient for Alexander to blame his father for any concessions to the Persians, but he—not Amyntas—married his sister Gygaia to a Persian (Bubares, son of Magabazus and distantly royal).* More likely he was already on the throne in the 490s but may have been quite young. He seems to have used the Persian presence to further consolidate the (new) Macedonian kingdom—against Paionians and others—adding territory as far away as Amphipolis, at least temporarily, and thus, getting hold of both silver and gold mines to mint coins. The Echedoros River also held gold. All the gold in pre-Alexander Macedonia was pacer mining (panning), not from the gold mines of Mt. Pangaion. Yet gold, while present in the rivers, only became important in graves in Macedonia c. 570…it’s part of that startling shift in burials that we see.

We also don’t know exactly when Alexander I died and Perdikkas took over. He was still king at the end of the Persian Wars in 479/78, but dead by 450. His death may have been closer to 460, or even earlier. So his reign was probably more like 30-35 years. Perdikkas perhaps reigned longest of all—one reason he’s exceptional. I wonder if the Peloponnesian War itself may have contributed to his success: for all he had his challengers, if Macedon wanted to survive as an independent political entity, they needed to rally around him.

Yet he faced his share of opposition from other Argeads as well as the very powerful Upper Macedonian kingdoms of Lynkestis (Lynkis) and Elimeia, not to mention predatory Illyrians. That’s why Perdikkas sought an alliance with Brasidas of Sparta, but apparently couldn’t even control his own troops enough to keep them from deserting when facing Illyrians. That earned Brasidas’s wrath. As a result, Perdikkas (coin below) had to make nice with Athens.

That’s just one example of Perdikkas’s deal-making during the war. He had quite a job of diplomatic shuffling—no doubt learned from Daddy Alexander. Neither had a kingdom anywhere near strong enough to fend off Persia, or Athens and Sparta later. The fact Perdikkas didn’t end up a client king to either Sparta or Athens is a testament to his diplomatic skill.

Perdikkas’s eldest son Archelaos wasn’t the “illegitimate” son of a slave but of a lesser wife, which is why the younger (unnamed) son initially inherited. Archelaos quickly did away with him (plus an uncle and cousin), then proceeded to continue the modernizing work of his father and grandfather. Until he got run through in a hunting “accident.” After that, the kingdom dissolved into a mess.

The problem of a fast turn-over of rule owed to their inheritance system: any Argead had a claim on the throne. Kings also practiced royal polygamy, although two wives (at most three) seems to have been typical until Philip II. In some ways, it worked well, as it produced multiple heirs from which a strong king could emerge (by surviving).

That was also its problem: no clear method of succession, even if the sons of higher-status mothers apparently had a leg-up. Perdikkas himself was not Alexander’s eldest son. He had two older brothers and two younger ones. Yet either his mother was the most prominent or he showed the most promise (or both). Despite Archelaos’s age and apparent ability, he was initially passed over, although Plato (who tells the story) means to paint Archelaos poorly. That doesn’t mean he didn’t kill competing Argeads to take the throne. So had his father, and probably grandfather too (we just don’t hear about it).

Yet Archelaos’s unexpected death led to a continuing crisis until Amyntas III, Phil’s dad, took and kept the throne. He came from a collateral Argead line descended from Alexander I’s youngest son. The other lines killed each other off. For all Amyntas wasn’t a terribly prepossessing king, he managed not to die. But he, too, was run off his throne at least once, maybe twice. When he did die, it was in his bed of old age—not a common thing for Macedonian kings. His reign was the first tolerably long one after Archelaos, over 20 years.

By the time Philip came to the throne, there weren’t many Argeads left thanks to the catch-as-catch-can method of succession: Philip’s two older brothers were dead and all three of his half-brothers. It was down to just him and his brother Perdikkas III’s infant son: Amyntas.

This is the inevitable problem when lacking a clear succession. Yet a clear succession can create its own problems with incompetent heirs, who don’t always recognize they’re incompetent. The free-for-all gave a better shot at a strong king—ostensibly why it developed—but it also meant the kingdom ran out of “spares” after a couple generations. They went from more Argeads than you could shake a stick at following Alexander I’s death, down to just three at Philip’s death, and two at Alexander’s death** in a matter of 5-6 generations. Within those 5-6 generations, 12-14 kings reigned! And we have no idea how many brothers/cousins/uncles Alexander I had, and perhaps killed, before he became king. We hear only about the one sister.

Stability was not a hallmark of the Argead dynasty.

——

* The story of Alexander killing Persian emissaries is much later fictional propaganda. Didn’t happen.

* Alexander’s son Herakles by Barsine might count as a third, but the army doesn’t seem to have considered him viable for whatever reason.

#ancient Macedon#ancient macedonia#Argead Macedonia#Temenids#Argeads#Alexander I of Macedon#Perdikkas II of Macedon#Gygaia#Archelaos of Macedonia#Philip II of Macedonia#Philip of Macedon#Alexander the Great#ancient Greece#Persian Wars#Greco-Persian Wars#Peloponnesian War#Brasidas of Sparta#Classics#tagamemnon#asks#Early Macedonian History

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herodotus on the role of Sparta in the Persian Wars

"What were Herodotus’ views on Sparta as an ally in the Persian wars?

Answer by Matthew A. Sears

Herodotus, on the one hand, thinks Sparta is an indispensable ally since in his account it is unlikely the Battle of Plataea, the final decisive battle of the Persian invasion of Greece, would have been a Greek victory. In his evaluation of that battle, Herodotus says that the Spartans excelled all in bravery (9.71) and took on the strongest part of the Persian force. That said, Herodotus does say that the Athenians were most responsible for victory in the war as a whole, especially because of Athens’ fleet at the Battle of Salamis. He admits that this opinion will be unpopular, which suggests that most other Greeks thought that the Spartans were the most important member of the anti-Persian alliance (7.139).

On the other hand, Herodotus points out that on many occasions the Spartans were hesitant allies at best, and often outright unreliable. For example, the Spartans only sent their army to Plataea and gave up on the idea of hiding behind the Isthmus of Corinth after the Athenians – whose city had been burned twice in two years – reminded the Spartans of the generous terms the Persians now offered in exchange for Athenians giving up the fight (9.6-9). The Spartans, thus, took to the field out of fear of Athenian defection rather than concern for the allies that had borne the brunt of the war. The historian J. F. Lazenby, in his book The Defence of Greece, 490-479 BC (Warminster, 1993) aptly entitles his chapter about Sparta’s dallying while allied cities were repeatedly sacked by the Persians “With Friends Like These”. I think Herodotus would agree.

Even at Sparta’s supposed finest hour, the last stand of the Three Hundred at Thermopylae, Herodotus says they were acting selfishly rather than in the interests of their allies. While most Greeks thought that the Spartan king Leonidas sent away the other Greek allies out of concern for their survival once the defensive position at Thermopylae was about to surrounded by the Persians, Herodotus expresses the opinion that Leonidas was really worried that the allies’ spirit was not in it. More revealingly, Herodotus says that Leonidas wanted the Spartans to win glory alone, rather than share it with thousands of their fellow Greeks (7.220). Regardless of how one interprets the strategic and tactical factors at play in that famous battle – there has been a lot of disagreement on this point – hording all the glory for oneself is not the mark of a good ally. To be sure, Herodotus does commend the Spartans for their bravery and does not chastise Leonidas explicitly for this decision. Being concerned for one’s own glory above all other considerations is in line with how Homeric heroes approached war in the Iliad, after all.

To complicate things even further, not being too eager to join with fellow Greeks against the Persians could be a mark of good sense. When the Ionians were seeking help from the mainland for their rebellion against the Persian Empire, the Spartan king, heeding the advice of his daughter, Gorgo (the future wife of Leonidas, turned them away, preferring instead to stay out of it, 5.49-51). By contrast, Herodotus called the ships the Athenians happily sent to aid the Ionian effort “the beginning of evils for both Greeks and barbarians”, seeing as they led directly to the Battle of Marathon and the Persian invasion of Greece (5.97).

For a general treatment of how Herodotus understood relations between the Greek states, see P. Stadter, “Herodotus and the cities of mainland Greece,” in C. Dewald and J. Marincola (eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Herodotus, Cambridge, 2006, 242-256. For the idea that Herodotus wanted to warn his audience against trusting in the Spartans as reliable champions of freedom, see P. Stadter, “Speaking to the deaf: Herodotus, his audience, and the Spartans at the beginning of the Peloponnesian War,” Histos 6 (2012): 1-14."

From the site of Herodotus Helpline

Matthew Sears, Professor of Classics and Ancient History, University of New Brunswick, Canada

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Athenian Hoplite in the Persian Wars, twitter was curious about the cloth on the Aspis, so I will share that info here. The cloth is called an apron, sometimes curtain/skirt, and also referenced as "parablemata" it made an appearance in art and archeology around the time of the Persian Wars and fell out of use shortly after, suggested as an arrow catcher/deflector but I haven't finished reading up on it's full use.

#art#illustration#design#digital art#drawing#drawdrawdraw#character design#history#historical#artist on tumblr#artwork#hoplite#athens#athenian#persian wars#aspis#shield#parablemata

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

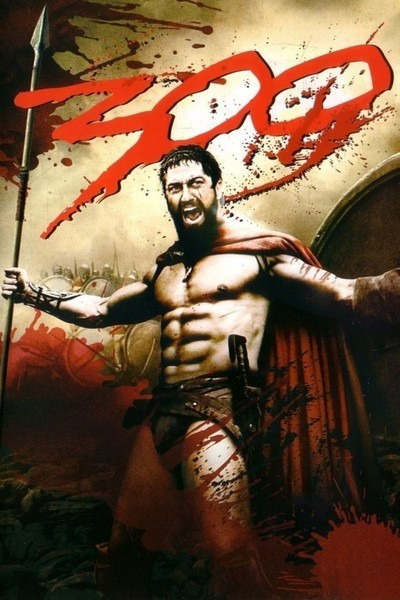

300: The Battle of Thermopylae and the Persian Wars

Sara, Luke, and Sam take their first dive into ancient history, rather than myth, this week with the 2007 violent, machismo-soaked 300! Learn all about the Persian Wars and Spartan life while enjoying topics of discussion such as: jock rock as a movie, fun ancient instruments, and the Greeks' aversion to pants

#Greeced Lightning#Greek Mythology#300#Persian Wars#Battle of Thermopylae#history#mythology#ancient greece#educate#greek mythology#comedy#classics#history podcast#myths#Education podcast#educate yourselves#prepare for glory#Spotify

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My roman empire is that people should make more big budgeted musicals about the ancient civilizations. We can have an Epic of Gilgamesh musical, the Trojan War, and any ancient story that was passed down through song for generations.

I wanna hear our ancestors come alive again and hear the beautiful words and stories that they’ve so passionately sang and written about-for us not to forget about them.

#roman empire#epic of gilgamesh#trojan war#achilles#ancient history#ancient civilizations#greek poems#middle eastern poems#persian poems#musicals#epic the musical#literature

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

When you wind up putting a bunch of research into a random side character you created for comedy reasons because you need to justify why he's in London in the first place

#rambles#oc posting#fallen london oc#that's what i get for making him syrian/ottoman#character: carlo michail#my third multilingual character- 3/3#my boy speaks persian let's go#and his dad is a veteran of the egyptian-ottoman wars

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Name: Darth Maul

Trainer Card Number: 806

Gender: Male

Series of Origin: Star Wars

Type Specialty: Dark

Hisuian Arcanine: He's a Zabrak, so he has all the spikes on his head

Mawile: Darth Maul-wile, I thought it was funny

Meowstic: His mom, Talzin

Crawdaunt & Hydreigon: Two dark types that can learn Double Hit, a reference to his double sided lifesaber

Alolan Persian: His profession as a crime lord

#pokemon#pokémon#star wars#darth maul#zabrak#dathomir#hisuian arcanine#mawile#meowstic#crawdaunt#hydreigon#alolan persian

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Officer's Uniform of the 3rd Bombay Light Cavalry from the British Empire dated to 1857 on display at the National Army Museum in London, England

This uniform belonged to Captain John Malcolmson who participated in the capture of the port of Buchire in December 1856. At Khoosh-ab, 8th February 1857, the largest battle of the Persian War (1856 - 1857), he won the Victoria Cross after his unit charged and broke a square of Persian infantry.

This conflict was due to the British and Russian Empires fighting for control over Persia, especially what is now modern day Afghanistan in what was called the Great Game. While Britain and Russia did not fight directly they caused conflicts in the region that led to the deaths of many of the people living there.

Photographs taken by myself 2024

#military history#art#uniform#fashion#cavalry#british empire#india#indian#persian war#19th century#victorian#national army museum#london#barbucomedie

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

best thing about the pluto anime is that my friend and i now refer to ptsd exclusively as "persian war syndrome"

#don't get me wrong i do genuinely love the series but calling it “persian war syndrome”.......#astro boy#pluto#netflix pluto#pluto anime#tetsuwan atom#mighty atom#memes#onward and queueward

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Themistocles before he deflected to Persia vs after...

So yeah, basically one of the most prominent Greek general from the Greco-persian wars was accused of being a traitor (till this day it's unclear if the accusations were accurate or not) and deflected to Persia to save his ass. He also became friends with the Persian King and a ruler in one of his satrap.

I imagine that the food must have been amazing in Persia.

#greece#ancient greece#persian#themistocles#greek history#greco persian wars#digital art#artist on tumblr#ancient persia#tagamemnon

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Persian Gulf Inferno (Innerprise, 1990)

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello Dr. Reames! Why do you think Alexander never set his sights on the conquest of Sicily - a rich island with longstanding Greek presence? Is it because when he came to the throne the plan to invade Persia was already on its way? I understand that Rome was a backwater town at this point and that Persia was the bigger prize, but Sicily always remained rich and hotly disputed

Inertia had a lot to do with Alexander’s choice, plus SIZE of the conquest, plus a plausible reason for the attack. I’m going to address these backwards.

Sicily, at least in the east, was—as you note—Greek, it’s largest city, Syracuse, Corinth’s most famous (and successful) colony. If conquest was still a valid reason for war in his world, increasingly parameters were put on it. We may understand these as window dressing concealing motives often economic (“follow the money,” ancient version). Yet by the 4th century, attacks on “fellow Greek” city-states needed some sort of rationale beyond naked ambition—often a current or historical beef.

Hence, Philip’s reason for attacking Persia (all about the money) was vengeance for the Greco-Persian Wars of over a century prior.

Another example, with Sicily in particular: Athens attacked Syracuse during the Peloponnesian War because she wanted Sicilian timber (for naval construction), after Brasidas of Sparta had convinced Perdikkas II of Macedon to cut off Macedonian timber—which had been Athens’ supply since the Greco-Persian Wars. Yet Athens justified the attack because Syracuse was a daughter-city of Corinth and Corinth was a member of the Peloponnesian league. Not to mention the war began due to Athenian-Corinthian aggression. So, by extension, Syracuse was tagged as an enemy of the Delian League (e.g., Athens’ not-so-covert empire), and ripe for hostilities.

Alexander didn’t have a ready-made excuse to attack Sicily. He probably could have found one, if he’d really wanted to, but this brings me to my second point.

Sicily is just not that big. And if some of her cities were wealthy enough, they didn’t begin to compare to Persia. When it comes to Alexander, “Think small” was never his modus operandi. LOL. Sicily would have been regarded like the Greek city-states of Anatolia (Asia Minor): a worthy acquisition…on the way to Bigger and Better. Yet Sicily lay west…not on the way to Bigger and Better. Just then. (more below)

Last, and the real reason: simple inertia.

Persia was the campaign his father had planned for probably a decade, and had fought south Greece to line up support for, culminating in the Battle of Chaironeia and the League of Corinth. Alexander did have to spend his first two years re-pacifying the Thracian and Illyrian north, not to mention re-fight Thebes to keep the south quiet … but PERSIA was what he’d been hearing about for years—what all Philip’s alliances were formed to pounce on.

To suddenly change and set his sights west on Sicily wouldn’t have made much sense, not to mention it would have alienated some of the city-states he needed (particularly his naval allies). He couldn’t have sold it as a “Panhellenic” crusade in revenge for the Greco-Persian War.

So, basically, I doubt it would ever have occurred to Alexander to sail west to attack Sicily when Persia was the bigger—and long planned upon—prize.

Now, let me add that—if academic speculation is correct and Alexander was setting up a campaign against Carthage near the end of his life—it’s quite likely that Sicily, and especially Syracuse, would have figured into that…but as allies, just as later with Rome. Carthage had long held the western part of Sicily, and struggled with the Greeks in the east for control of the whole. Conflicts with Carthage are why Syracuse invited in Rome for what became the First Punic War.

By the end of his life, and after Agis’s Revolt was crushed, Alexander was such a power, the Greek city-states had mostly given up opposing him. They contented themselves with snarky remarks and symbolic gestures—until after ATG’s death, when they rose up to try and oppose Antipatros in the Lamian War…which failed.

Yet if we could suppose Alexander had recovered from his last illness and did attack Carthage, Syracuse (et al.) would have been all over that. They’d have stood to benefit handsomely in territorial acquisitions. And at that point in time, Alexander probably was the only power that could have beaten Carthage on the water.

Hope this helps to explain why Alexander’s focus was always Persia.

A last thing: the nature of the Greek landscape, with the formidable Pindus Mountains down the center, had divided the peninsula east and west for centuries. The city-states on the east fronted the Aegean Sea, while those on the west fronted the Corinthian and Adriatic Seas. This affected both colonization and conquest ambitions. So eastern city-states tended to look east and western (including the Peloponnesos) tended to look west.

Macedon looked east. By contrast, Epiros looked west. That’s why Alexander of Epiros went to Italy while his nephew went to Persia. Never underestimate the impact of simple geography on history in the ancient world.

#asks#ancient Sicily#Syracuse#Alexander the Great#ancient Macedonia#ancient Greece#Alexander the Great's campaigns#Philip of Macedon#ancient Persia#Peloponnesian War#Greco-Persian War#Alexander the Great's ambitions#Classics

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Xerxes' Homer

Johannes Haubold "Xerxes' Homer" in Cultural Responses to the Persian Wars: Antiquity to the Third Millenium, Oxford University Press 2007.

"Abstract

This chapter argues that the reception of epic in wartime and post-war Greece was affected by an extended dialogue between both cultures. The Persian leadership used Homeric epic, especially the Iliad, in order to justify imperial expansion to the Greeks in their own cultural terms, just as they appropriated Babylonian and Judaic visions of history in order to validate their expansion elsewhere. Drawing on the Herodotean evidence for the Persians' use of Greek oracle-mongers, and especially his account of Xerxes' visit to Troy, which presented the king as the champion of Troy, seeking revenge for its downfall, the chapter suggests that Xerxes' Iliad consisted of a set of wholly new glosses on familiar topics, pro-Persian interpretations, and selective enactments."

According to the review of this chapter of the volume by Johanna Akujärvi (https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2007/2007.12.36/ ):

"Herodotus’ Histories famously begins with an account of how learned Persians attributed the origins of the conflict between Greeks and Persians to a series of abductions of women starting with the Phoenicians taking Io and culminating with the Trojans seizing Helen which the Greeks avenged by capturing and destroying Troy (1.1-1.5). Are this and similar passages merely a “projection of Greek thinking on to non-Greeks” (p. 50) as is commonly assumed, or are such passages in the Histories a reflection of the actual existence of a Persian take on the Trojan War, and perhaps even a particular Persian interpretation of the Homeric epics? In the chapter “Xerxes’ Homer” Johannes Haubold argues — quite plausibly, with parallels to Persian rewriting of Babylonian and Judaic traditions — for the latter alternative, though one should keep in mind that the more he ventures into particulars the more uncertain the argument gets (as Haubold himself indicates). Haubold demonstrates that the Persians and their Greek expert advisors had every reason to attempt to control the shape and meaning of important local texts, so that the conflict could be explained and justified in terms familiar to the Greeks. Haubold reconstructs the Persian narrative of the conflict along these lines: “a Greek from the mainland (Peleus) rapes the goddess Thetis, setting in motion the fateful events that eventually lead to the clash between Achaeans and Trojans. In a second step, a Greek army sets out from the mainland, sacks an imperial city (Troy), and offends the local deity, Athena, in the process.” (p. 56)1 Both the deity and the unjustly sacked city of Troy finally find their champion in Xerxes. Further, Haubold argues that the Iliad — since no Ionians are mentioned among the Achaean contingents in Iliad 2 and what is more, Miletus is mentioned as fighting with the Trojans — may have been used to strengthen Ionian loyalty and as an argument for the idea of a Panasian army in a campaign against the Greeks in Europe. The Greek reaction, a creation of “Homer the Greek patriot” (p. 61) can most notably be observed in the re-enactment of the heroic epic tradition in Attic tragedy, and other traditions, such as the Athenian epitaphioi logoi in which the Trojan War is linked with the Persian Wars in a struggle of ‘us against them’.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

you guys need to understand i WANT to draw kalluzeb but Zeb is so weird looking that i physically can’t

#i’ve TRIED to draw him he is beyond my skill level#he’s like an owl a persian cat and a mushy grape had a baby#i love him tho#star wars#the clone wars#rebels#alexsandr kallus#agent kallus#zeb#kalluzeb

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

18 notes

·

View notes